Author:

Knut K. Wimberger

Short summary:

This essay calls upon the reader to consider human resources as natural resources and the human species as a keystone species which can destroy and create ecosystems. Integrating human ecosystem services into the global economy requires a fair and decentralized remuneration which empowers individuals to contribute to a solution of the climate crisis. The introduction of a universal basic income which complements a shrinking labor market and distributes the productivity gains harvested through automation and digitalization is a solution to the environmental and social crisis.

On October 22, 2020 The Economist reported that an increasing number of African nations engage NGOs to manage their natural areas. Some 14% of the continent’s land has been categorised as protected, according to the World Database on Protected Areas (see map). The protected designation belies reality, however. Most such areas are managed by cash-strapped government wildlife authorities. Winning the support of people on the edge of the park has been crucial to succeed in their operation. It is therefore probable that more African governments will form partnerships with private bodies to protect ecosystems, bring in donor cash, and help protected areas raise a revenue of their own, through tourism and other ventures.

The question remains though how these private bodies will gain the support of people living on the edge of natural areas. Sustainable tourism initiatives must not stop at protecting wildlife areas but must encompass human societies that are part of the larger ecosystem. Turning natural areas into educational spaces and giving the local population access to quality training to become Nature Guides could integrate the local communities into a larger concept of wildlife protection. Remunerating locals fairly for engaging in sustainable agriculture, i.e. not according to market prices and for cash crops only would be another possibility. The crucial step to make such a transformation possible is, however, a quantum leap of how we perceive the role of the human being.

There is a traditional understanding of ecosystem services: varied benefits to humans gifted by the natural environment and from healthy ecosystems. This understanding implies that the human being is different from these ecosystems and only on the receiving end. Man has, however, always been a part of nature and was separated from nature only by means of a perverted culture. This process of human alienation from nature has been symbolically explained in Adam and Eve’s expulsion from Eden. Making humans part of nature again, empowering each single human being to perform and get involved in ecosystem services, is the only way to sustainably protect African national parks and the world at large. In a way, making the human being capable of performing ecosystem services is not only ecological but also a spiritual atonement. Now, facing the 6th mass extinction, more than ever.

When I contemplate a painting like the one above by Johann Wenzel Peter ("Paradiso Terrestre") from around 1820 which is now in the Vatican Museum, I don’t think of Adam and Eve or whatever forbidden fruit they might have eaten, but of biodiversity collapse and our forgotten role and responsibility in creation at large. The sheer number of different animals seems to reflect how the global wildlife body mass was once in comparison to the global human body mass. Its title “Paradiso Terrestre” (literally the Garden of Eden) implies a Judeo-Christian concept. City dwellers from Germany or Japan who seek forest baths to reconnect to nature have become a mainstream and cross-cultural desire of mankind which seems to reflect that we have lost something somewhere on the path to modernity.

Environmentalist and poet Gary Snyder writes in The Practice of the Wild, that the word nature has two slightly different meanings in our modern vocabulary: One is “the outdoors” – the physical world, including all living things. Nature by this definition is the norm of the world that is apart from the features or products of civilization and human will. The machine, the artifact, the devised, or the extraordinary (like a two-headed calf) is spoken of as “unnatural.” The other meaning, which is broader, is “the material world or its collective objects and phenomena,” including the products of human action and intention. Science and some areas of mysticism rightly propose that everything is natural. In this light, there is nothing unnatural about NYC, or toxic wastes, or atomic energy, and nothing – by definition – that we do or experience in life is “unnatural.”

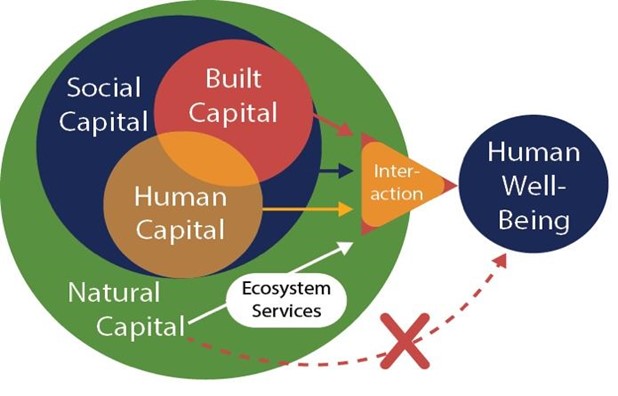

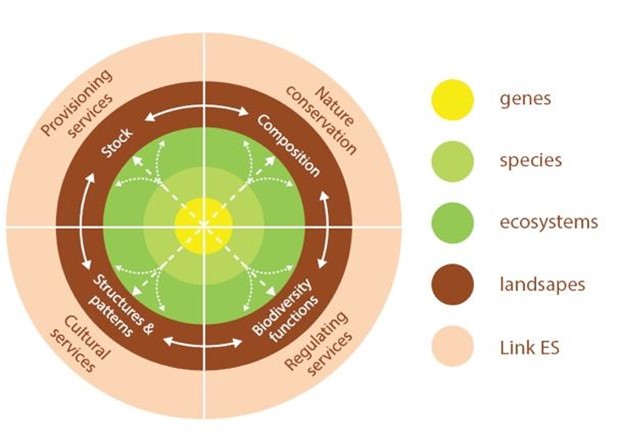

Forest baths, despite their positive effect upon the human being, keep us in the passive consumer role. This observation helps us to focus on the economic dimension of how we interact with nature and how a re-integration of mankind into nature could work. The above graph reflects the common understanding that ecosystem services are only performed by natural capital and that natural capital is different from human capital. It is also interesting to observe that this graph focuses on human well-being only. In any planetary ecosystem, the well-being of all living and non-living matter needs to be included.

Benjamin Burkhard and Joachim Maes summarize the history of ecosystem economics for us: The ways nature provides benefits to humans are discussed throughout economic history from the classical economics period to the consolidation of neo-classical economics and economic sub-disciplines specialised in environmental issues. Some of the classical economists explicitly recognised the contribution of nature rendered by 'natural agents' or 'natural forces'. However, although they recognised their value in use, they generally denied nature's services role in exchange value, because they were considered as free, non-appropriable gifts of nature. Physiocrats’ belief that land was the primary source of value was followed by the classical economist's view of labour as the major force behind the production of wealth.

Marx considered value to emerge from the combination of labour and nature: "Labour is not the source of all wealth. Nature is just as much the source of use values (and it is surely of such that material wealth consists!) as labour, which itself is only the manifestation of a force of nature". In the 19th century, however, industrial growth, technological development, and capital accumulation led to changes in economic thinking that caused nature to lose importance in economic analysis. By the second half of the 20th century, land or more generally environmental resources completely disappeared as a production function and the shift from land and other natural inputs to capital and labour alone and from physical to monetary and more aggregated measures of capital was completed. In the second half of the 20th century, environmental problems became a topic of interest to some economists who founded the Association for Environmental and Resource Economists in 1979. The undervaluation in public and business decision-making of the contributions by ecosystems to welfare was partly explained by the fact that they were not adequately quantified in terms comparable with economic services and manufactured capital.

In lack of a better term, let’s talk about the Eden concept of ecosystem services, to describe the human being as part of the natural world and active provider of ecosystem services. It is quite obvious that some farmers who maintain agricultural areas like the Barolo vineyards in Northern Italy’s Piedmont province perform a kind of ecosystem service – assuming that they comply with honest standards of sustainable farming. They have tended to soil and plants for centuries in a way that renders the hills of the region into marvelous landscape art. It is important to emphasize that the local population has a high stake of responsibility, but even more importantly: pride and financial reward in performing this role.

It is highly questionable if different private bodies with distinct organisational forms and management practices would be capable of integrating local people living at the edge of Africa’s natural areas considering the general economic situation. It is even less likely that these NGOs will find a consensus on how to fairly empower individuals to perform ecosystem services. Economically disadvantaged regions require a global and standardised solution to drive a transformation towards the provision of human ecosystem services. Such a global system needs to be flexible enough to integrate a local dimension and grow individual pride, self-worthiness, and meaning through one’s contribution.

In an era when labour markets are under an unprecedented transformation, we need to question the nature of human labour and its impact upon the planet as a single ecosystem. If we perceive human labour as a natural resource which can be allocated to either destructive or constructive services, then it becomes obvious that millions of office workers in the third sector of industrialised nations do not contribute to the wellbeing of people and the planet, but accelerate the depletion of natural resources by driving consumption. Similar statements can be made about workers in industrial agriculture and manufacturing industries and even more so about all those, whose potential contribution is rendered irrelevant because they are not integrated into the global economy at all and their lives are like unused and barren land from birth to death.

Youth unemployment and extended but mostly futile schooling periods drive many young people into hopelessness and children into behavior which is diagnosed as attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder when the cause is simply a lack of meaning and contribution to something that matters in a world which has become nihilistic and apathetic to the human need of making sense of one’s existence. Covid-19 has accelerated this human drama which our civilisations continue to ignore. A recent study confirms that mental health during the corona crisis deteriorated in particular among individuals lacking meaning and self-control and indicates that younger generations are more affected than older ones. However, it fails to provide a systemic solution on how to give back meaning to the affected parts of society.

A lockdown situation during Covid-19 resembles the concentration camp experiences which pushed neurologist Viktor Frankl to write the book Man’s Search for Meaning immediately after WWII and develop the third Viennese School of Psychotherapy. Logotherapy is based on the premise that the primary motivational force of an individual is to find meaning in life. It might sound over-simplified, but as humanity faces the corona crisis, the biodiversity crisis, the education crisis, the climate crisis, meaning can be given easily by letting people participate in and remunerate them for being part of in the solution to the multiple crises by paying them a conditional universal basic income.

Human resources need to be considered natural resources in order to make this happen. They need to be activated and utilised by integrating them into the global economy through a fair and decentralised system that empowers individuals to contribute meaningfully. The solution to the climate crisis is also a solution to the social crisis: the introduction of a universal basic income which complements a shrinking labor market and distributes the productivity gains harvested through automation and digitalization fairly in a social and environmental contract.

How did Carl Sagan once write in Cosmos:

Human history can be viewed as a slowly dawning awareness that we are members of a larger group. Initially our loyalties were to ourselves and our immediate family, next, to bands of wandering hunter-gatherers, then to tribes, small settlements, city-states, nations. We have broadened the circle of those we love. We have now organized what are modestly described as super-powers, which include groups of people from divergent ethnic and cultural backgrounds working in some sense together — surely a humanizing and character building experience. If we are to survive, our loyalties must be broadened further, to include the whole human community, the entire planet Earth. Many of those who run the nations will find this idea unpleasant. They will fear the loss of power. We will hear much about treason and disloyalty. Rich nation-states will have to share their wealth with poor ones. But the choice, as H. G. Wells once said in a different context, is clearly the universe or nothing.

Further Reading:

▪ Gary Snyder, The Practice of the Wild

▪ Sunny Fitzgerald, The secret to mindful travel? A walk in the woods

▪ Why You Really Should Visit Italy's Outstanding Barolo Wine Region

▪ 6th mass extinction

▪ Tatjana Schnell and Henning Campe, Meaning of Life and Self-Control Buffer Stress in Times of Covid-19

▪ Viktor Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning

▪ Martin Ford, The Rise of Robots

▪ Carl Sagan, Cosmos