Author:

Knut Wimberger

Short summary:

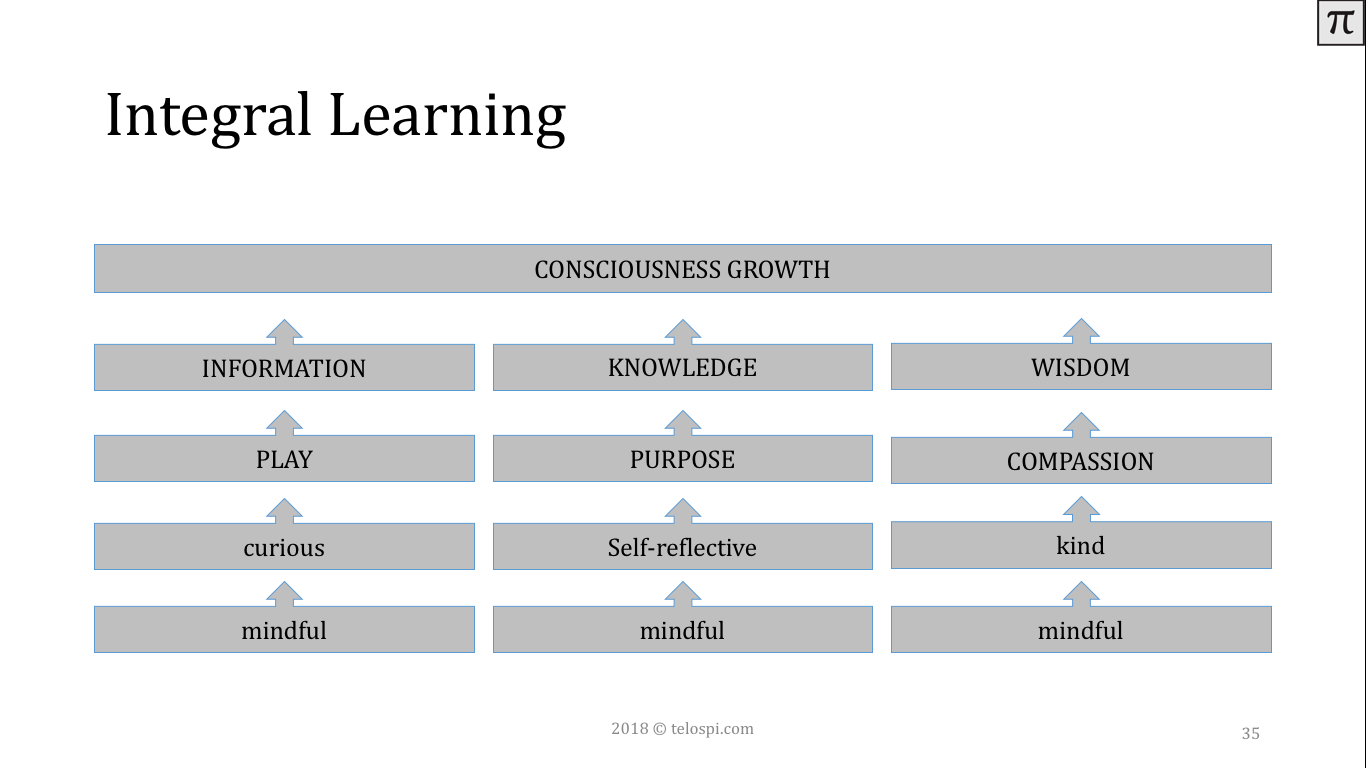

We need to find a new form of learning. One which engages children through play and helps them to absorb information in an enjoyable manner. A form of learning which instills a sense of purpose into them; and a form of learning which teaches them compassion for self, others and the planet.

Unlocking the Human Potential through Play

First day traveling with my son from Shanghai to Vienna. He hasn’t been back to Austria for three years and is now almost seven. Shanghai is the only world he knows. Austria is new to him and with a childlike spirit he observes the differences between where he grew up and where his European ancestors hail from.

The confusion about his not yet formed identity becomes already apparent on the plane when we play a memory game about national flags handed to us by the flight attendant. He turns around the German flag and I ask him if he knows which country these colors represent. His unmistaken answer is: Shanghai.

Such is the child’s perception of nationality until a sense of self is merged with a sense of nation: it does not think about territory or borders, but only about a space which is filled with love and care, a community in which it grows up and strong. We happen to spend a good deal in a Shanghai based, German dominated community of families with still young children. And such is Isak’s perception.

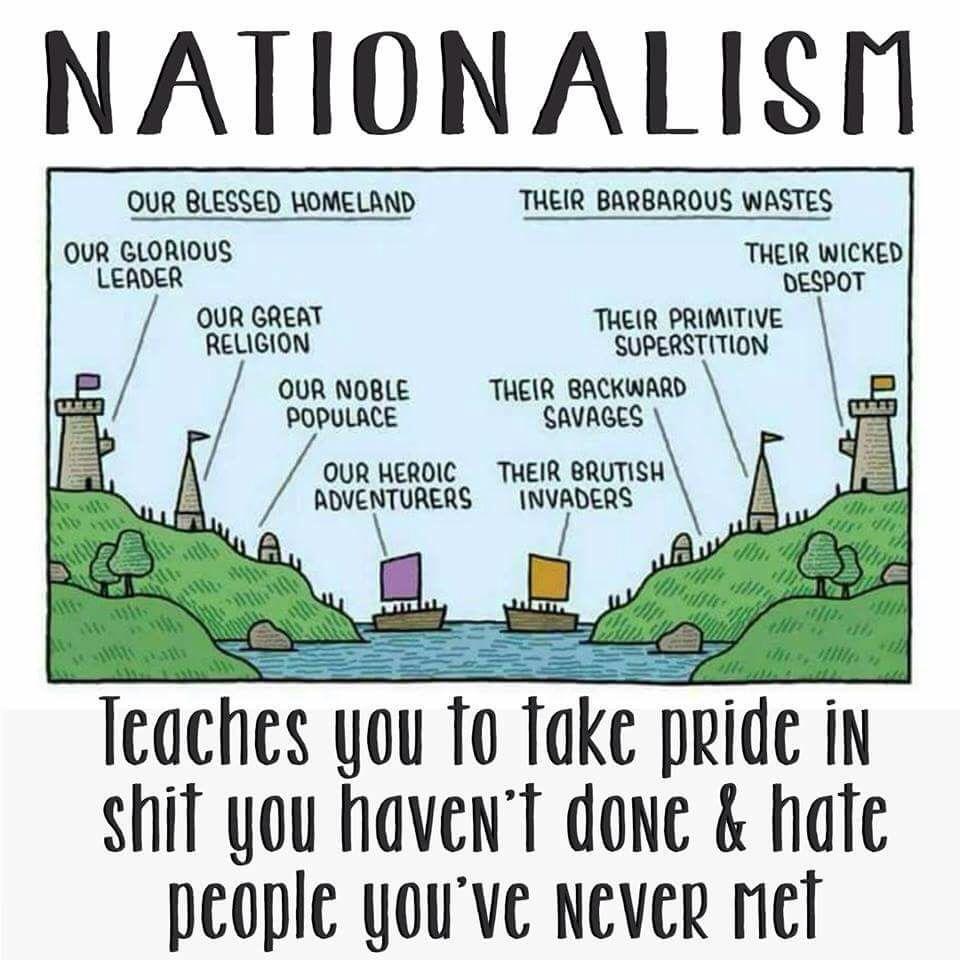

As children grow older they continually notice the differences between cultures and absorb the concepts which are instilled in them. Nationalism is insidious because it takes a back door into the child’s heart and as such creates a lasting concept of you and me, of what separates my world from yours.

Jesus Christ once said, blessed are those who knock down the walls which separate us. He didn’t say it, but I guess he induced: cursed are those who build walls which separate us.

Our daughter Zoe hums on the day of our departure in a joyous spirit the Chinese national anthem. A few minutes later she pulls out the notes, sits down at the piano and sings the anthem with a tune. I look at her bewildered and ask: Why do you do this? Her immaculate answer: because it is a beautiful song which we sing every day in school. But, Zoe, don’t you have any other songs to practice? Yes, yes, she says and flips to another book of music.

The great American anthropologist and poet Gary Snyder writes in The Practice of the Wild that it is our local songs and dances which governments first take from us in order to domesticate a subject. However, human nature craves for singing and dancing and can’t deal with the vacuum left behind. Neurobiologist Gerald Hüther wrote a great deal about the positive effects of singing. Our brain chemistry shows that joint singing stimulates the production of the hormone oxytocin and as a result causes bonding and a feeling of well-being.

Nationalist regimes recognized this early on and gave its citizens something back in return: the anthem with a daily ritual of flag hissing. Shanghai metro TV screens continuously a video of Chinese citizens, young and old, singing the anthem with wet eyes. State orchestrated love for the nation at the expense of the self, other nations and the planet.

The rites of passage which defined the communities of our ancestors made us bow to the spirits of nature. Nationalist rites make us bow to state authority. It might be this disconnection from nature, which is the root cause of not only social but also environmental destruction.

Isak and me get on the train leaving Vienna airport for Linz, my father’s hometown. The distance between Vienna and Linz is the same as between Shanghai and Hangzhou, roughly 200km. Half between the two cities over a card game of UNO Isak lifts his head and moans: Why is this train so slow?

I have nothing to answer and smile silently. He already seems to be used to Chinese 350 km/h bullet trains. Acceleration and alienation.

When we enter my brother’s apartment, Isak is confused: this looks different. This is not granddaddy’s big house he remembers from our last visit. Yes, you are right, this is where Alex lives, I explain to him. After a quick shower Isak demands to see his grandfather’s house, so we make ourselves ready for a short ride to the north of town.

I tell him to fill up his water bottle. He asks: Where? Looking for a water dispenser or an electric water cooker. I point to the kitchen tab. He stares at me in disbelief: You can drink this?

I smile again. Yes, you can. Water is very clean here.

On our ride to my father’s home, only 10k in total, we cross most of the town on a city highway. It takes longer than expected because of road works and a massive resulting traffic jam. I point out landmark buildings to our son. Isak takes everything in but says nothing.

We leave the city highway and turn into the municipal road which leads to a suburb. Isak lifts his voice and says in Chinese: 在路上怎么看不到警察?Why are there no policeman in the streets?

It is this last of his observations during this first day which troubles me most. A child recognizes within only a few hours what is probably the most important indicator of how a society operates and is organized.

Economist Damien Ma writes in his 2013 title In a Line Behind a Billion People that China allocated in 2011 624 billion yuan, i.e. over 6% of total public spending to domestic public security. That is higher than healthcare spending and higher than the national defense budget of 601 billion yuan.

70% went to domestic police and the paramilitary force, the People’s Armed Police (PAP), while the courts and judicial functions received a much smaller fraction. On matters of law and order, there isn’t much competition—order wins by a wide margin, at least in terms of resource allocation.

One wonders if under such frame conditions education can unlock the human potential or if society is in fact set up to lock in human consciousness.

Merics, a German think tank published in February 2019 a report in which the author argues that China struggles to boost innovation and balance conformity. The underlying survey shows that teachers must straddle a fine line between the needs of the children and the needs of the system.

We are aware that a national education monopoly collides with individual interests, that a nation’s strength weakens the individuum. Power corrupts purpose. However, we lack alternatives and put what is most precious to us, our children, into institutions which make marbles out of raw diamonds.

On June 7th, only a few days before we board our plane, Chinese high school examinations were held all over the country. I witness this spectacle every year right behind our downtown apartment on Yuyuan Road, where one of Shanghai’s elite middle schools is located.

This year, about 50 policeman, police motorbikes, armored vans and police cars slow down and direct the traffic in front of the school. They secure low noise levels to support the examinees’ concentration. But they also reveal how state power pushes its youngest citizens to give their best for the sake of the nation. State ordained intrapreneurship starts early on and society turns unnoticed by most into one large gulag.

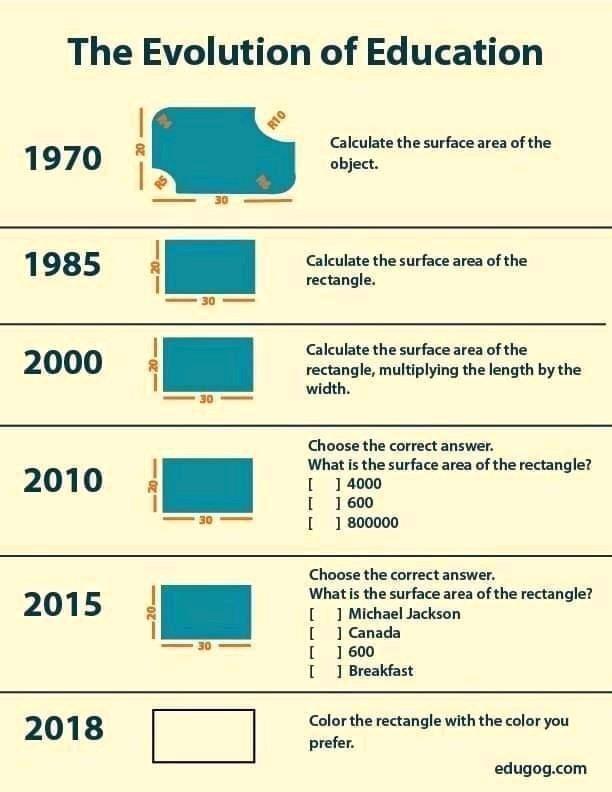

However, Western education systems don’t perform any better. One of the most popular TED talks by educator Ken Robinson explains that divergent thinking, the cognitive skill which is attributed to creativity decreases rapidly within almost every child as it progresses through compulsory education.

We wake up early the first morning in Austria. It is still night outside but the day is about to break. I take our son on a short neighborhood stroll and we come to stand under a huge tree burgeoning full of wild cherries. He asks in wonder: what is this? And makes me lift him up to pick a few dark red cherries on which he munches happily and with such a delight that my day is already made. It is not only a political system, but also metropolitan life which deprives children of nature and much more that is needed to become a whole human being.

We return to my brother’s apartment who is already up reading the newspaper at the kitchen table. Isak has forgotten about the cherries, but excitedly tells him about the field rabbit and the squirrel he spotted a few minutes ago.

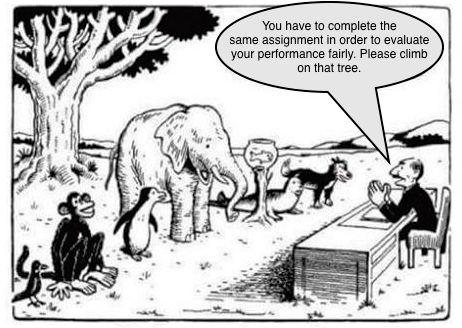

I grab Alex’s newspaper. It titles “Our students come in first place in a national comparison of high school graduation mathematics exams.” Austria has introduced only recently a centralized high school graduation system. Supporters contend that it makes examinations fair, transparent and achievements nation-wide comparable. With the entire Austrian population merely matching a Chinese second tier city and generally fewer students per class, one might think that this leaves still room for individual learning styles. But it doesn’t.

There is ample criticism. Most people believe that general education standards suffer from a centralized system as the above visualization shows. I am simply terrified by the trend of standardizing curricula and examinations even in my fairly prosperous home country when everything points at the requirement of personalized learning.

Less discussed but equally important is the negative impact on the teacher – student bond when standardized examinations reduce the teacher’s discretion in defining learning content and in emphasizing punctual examination results over the long term student performance. I still remember from my own high school days that most teachers tried to find a balance between a student’s average class engagement and finals to arrive at a final grade. It was not the final examination only which decided over a student’s fate.

A centralized examination system reduces human interaction and creates automatons which are supposed to work in an utterly competitive and strictly predefined setting. However, creativity directed at purposeful impact is nurtured in an organic and dynamic environment shielded by compassion and cooperation.

Isak shouts from the kitchen: Can I eat a pear? I haven’t seen a pear, I reply. He walks over to the other room I am in and shows me a Golden Delicious. That is not a pear, I tell him. It’s an apple. He shakes his head: no it’s a pear. Well, try it and you will see. He bites into the pear and smiles in disbelieve, “It is an apple!”

Now, we could say that this little incident is a metaphor for education. In Chinese fruit stores there is basically only one kind of apple: the Fushi, named after Mount Fuji in Japan. One has to go into delicatessen shops to get anything else. As a result, most children grow up believing that apples should always look like a red Fushi, while pears do always come in a standard yellow.

Stephen Johnson called this phenomenon in his book Where Good Ideas Come From the adjacent possible: the more parts are available, the more likely new things can be created; think e.g. of a soapbox race: you have to build your own race cart. Where will you have more inspiration; in your own basement or at a large junkyard? In Johnson’s words: The trick to having good ideas is not to sit around in glorious isolation and try to think big thoughts. The trick is to get more parts on the table.

The same is true from a systems perspective for a hermetically sealed off national curriculum or consumer products which are defined by corporate power structures instead of local communities. We have less parts on the table and are therefore less creative and conform more to whatever mainstream thinking is supported by the ruling class. In a globalizing world with global challenges this doesn’t sound like the environment which will produce solutions needed.

I retrieve a box of games from our basement and find Slotter, an MB game which I got some 35 years ago. Its box is old and the cover pictures tell a story of 70s fashion, but the game itself is in brand new condition.

We play it the next morning after breakfast. Isak is fascinated by the turning wheels and clearly absorbed by the game. I have to fight boredom after the second round but are amazed by his enthusiasm. He trains his fine motor skills by twisting and turning the game’s sprockets. He trains his sense of order and basic mathematical skills by moving the numbered coins through the slots. He learns but doesn’t realize it. That’s the power of play.

Sir Ken Robinson, the contemporary reformative pedagogue mentioned earlier, wrote in his bestseller The Element that a child’s talents are often deeply buried and need to be mined for like we mine ore or gems. However, he argues that our talents flourish once we are in our element.

Critics of Robinson point out that passion – the focal characteristic of one’s element - is not everything what it takes to find a fulfilling job in adult life: purpose is equally important. Journalist Mike Rowe explains in his Ted talk Learning from dirty jobs that this is certainly true. But, what if purpose and passion could be merged by play? What if the surge in attention deficit and hyperactivity disorders in children and burn outs in adults is the result of a spreading play deprivation?

Psychologist Barry Schwartz explains that intangible values of work have been exterminated from our collective conscious through the separation of labor and the capitalist system: your only reward for your work is your paycheck. Technology disappears when inefficient or obsolete, but an ideology like excessive capitalism is a human software building institutions and cultures which keep wrong, inefficient and overcome ideas in place and thus hamper development.

I argue here that these cultures are already built in early childhood because we deprive children of play.

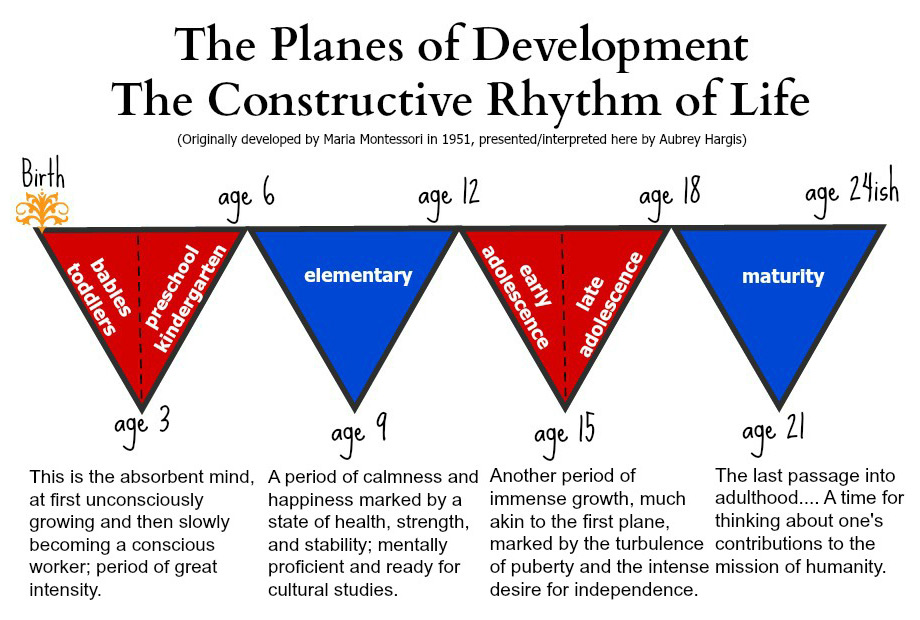

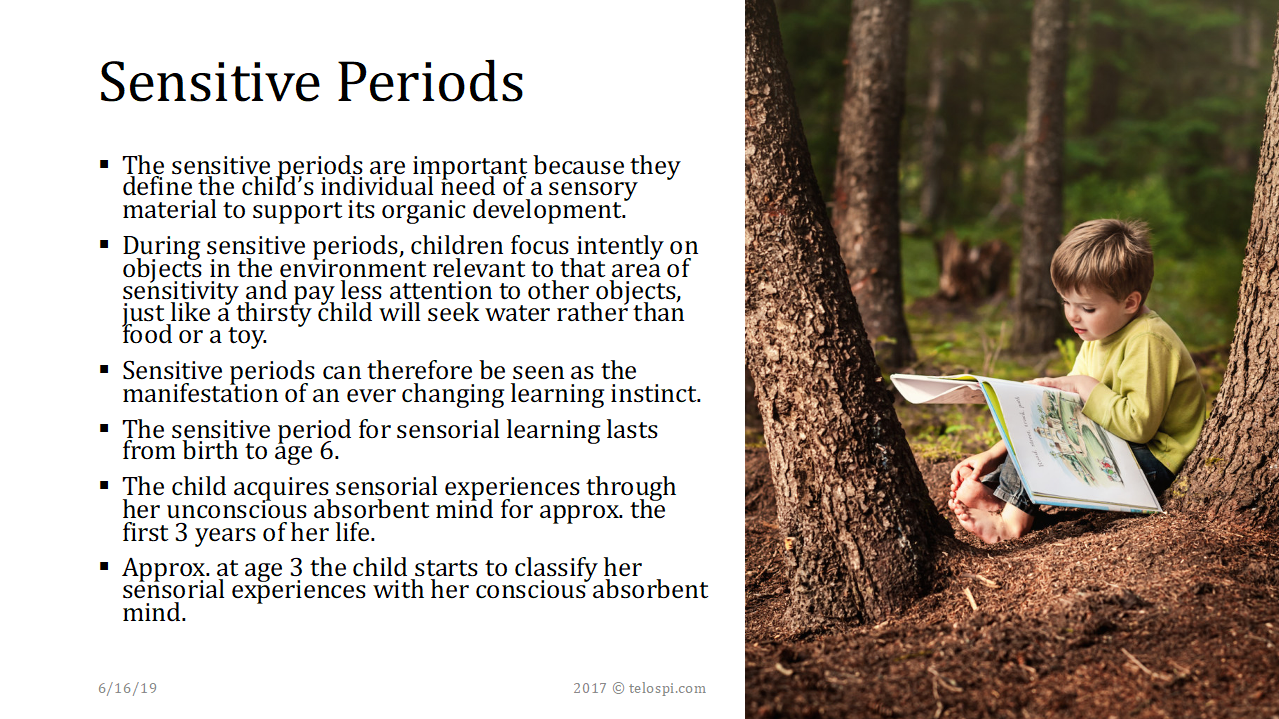

Maria Montessori, a 20th century reformative pedagogue, introduced the concept of sensitive periods embedded in planes of development lasting 6 years each. She pointed out that children require rather personalized observation than generalized education. Children whose learning needs are met during a sensitive period react with full attention and deepest concentration which comes closest to what psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi described as the state of flow.

Robinson’s concept of an individual element and Montessori’s concept of sensitive periods have without doubt a strong overlap. One could argue that finding one’s element is the result of the child’s learning needs being met during several sensitive periods. One’s element might be in other words the combination of several such childhood learning experiences.

Industrial education systems which push children in a competitive environment through a curriculum which is mostly presented in text books and increasingly through multimedia applications clearly reduce the chance that a child finds its element. It appears as if children have to learn more and more, but from a sensorial education perspective they actually learn less and less.

Student attention, interest and engagement is low. Stressed out teachers on the other hand can’t be blamed that they fail to listen to their students’ needs. These needs are to be satisfied with multidimensional and playful learning experiences. Supercharged classrooms, textbooks and screens stimulate only a tiny fraction of human nature.

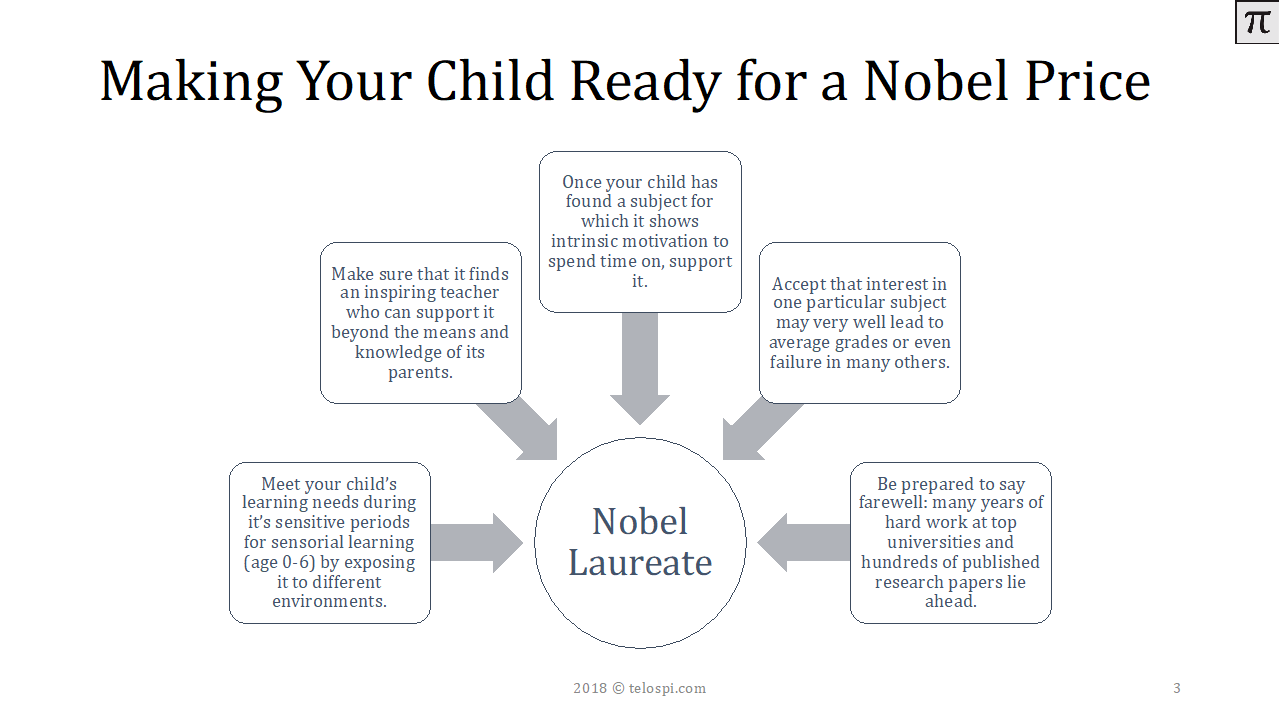

Larisa Shavinina, a researcher at Quebec University, conducted with her team a study on the biographies of Nobel Laureates. She identified three things which all of her research subjects have in common:

1. Exposure to a learning conducive environment during a sensitive period

2. Parents who support the child once interest in an activity has been recognized

3. Teachers who support the child beyond parents’ means and knowledge

Shavinina is a psychologist who focuses in her research on innovation and creativity in high achievers. Her international handbook on innovation is the most comprehensive and authoritative account available of what innovation is, how it is measured, how it is developed, how it is managed, and how it affects individuals, companies, societies, and the world as a whole. Innovation, however, is not well-being. I’d rather consult the Dalai Lama on the latter. In particular when it’s about the future of my children.

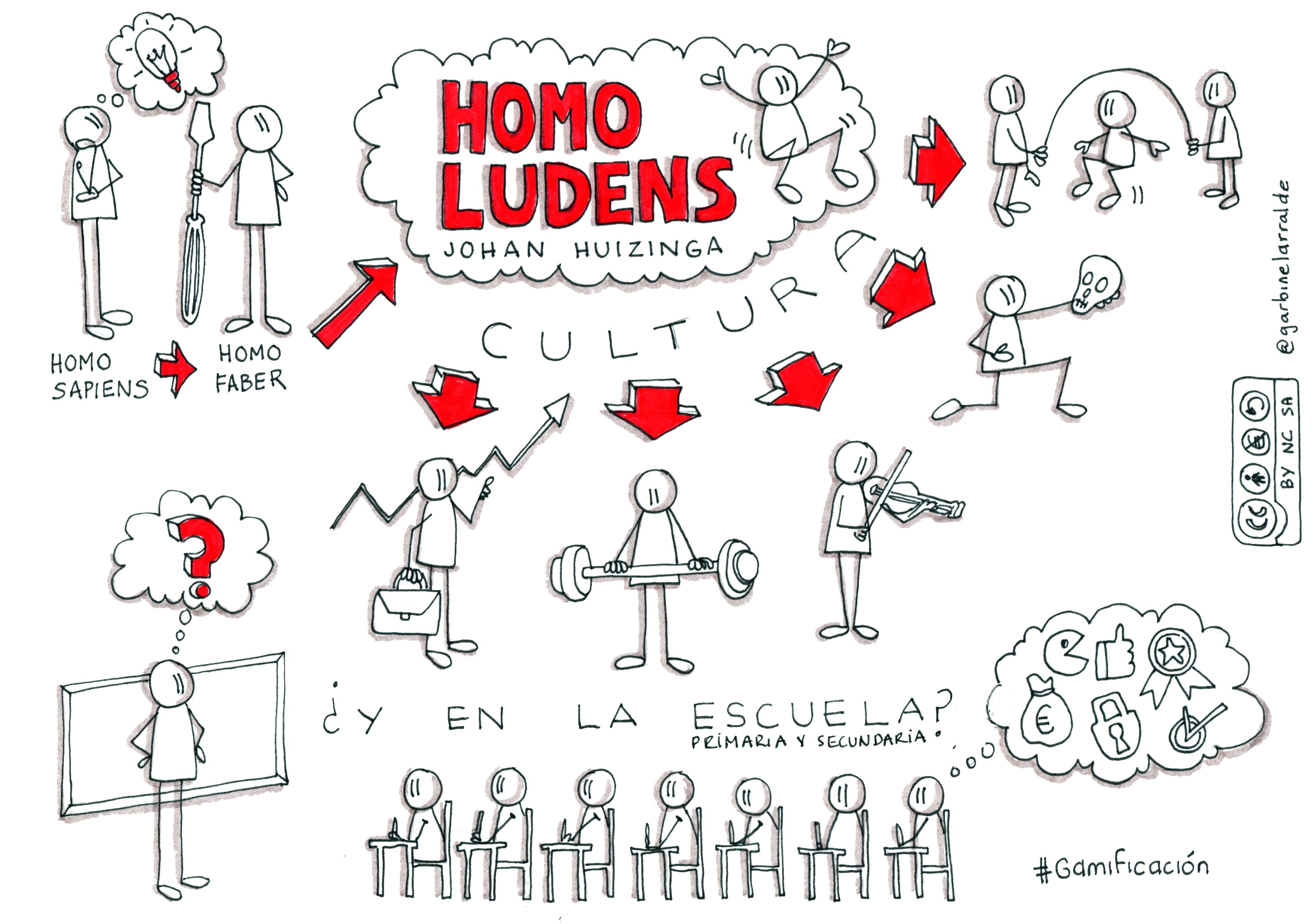

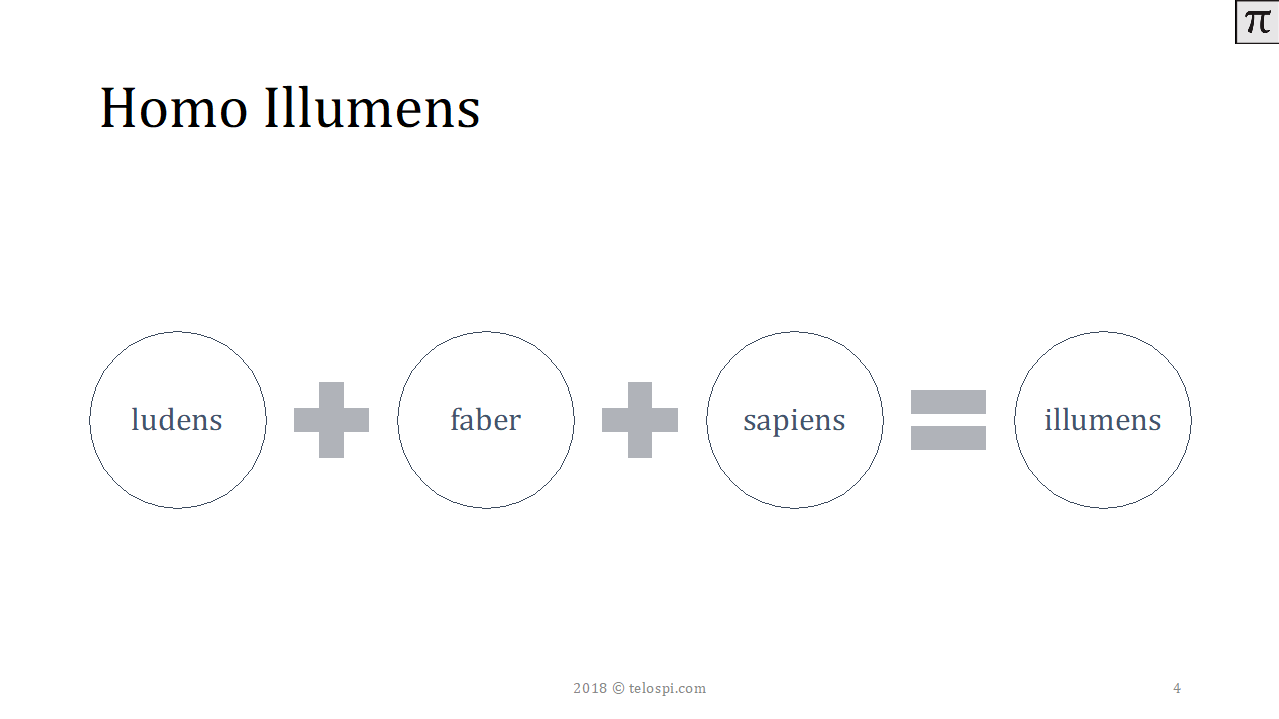

The irritation about Shavinina’s research sits deep. It’s there because it reflects a general culture shift. Our competitive knowledge economies have lifted homo oeconomicus into Mount Olympus while homo faber and in particular homo ludens have been condemned into Hades. The original meaning of homo sapiens has been forgotten long ago and taken hostage by homo oeconomicus.

We worship people who excel in science. We do so because modernity has merged science, technology and power. We do so because capitalism has a tendency to extract profit from planet and people by deleting passion, compassion and play elements from culture at large.

Children book author Michael Ende made this observation the main subject of his novel Momo, showing that excessive capitalism is fascist in nature and destroys everything without a clear price tag. Therefore, we no longer value healers, storytellers and clowns; people who have the talent to make us laugh, make us human and whole. We no longer understand that we all have these qualities and that they make our work enjoyable.

"So you've already squandered another fifty-five million one hundred and eighty-eight thousand seconds, Mr Figaro. We also know you go to the cinema once a week, sing with a social club once a week, go drinking twice a week, and spend the rest of your evenings reading or gossiping with friends. In short, you devote some three hours a day to useless pastimes that have lost you another one hundred and sixty-five million five hundred and sixty-four thousand seconds." The agent broke off. "What's the matter, Mr Figaro, aren't you feeling well?"

"No," said the barber, "-- yes, I mean. Please excuse me. . ."

"I'm almost through," said the agent. "First, though, we must touch on a rather personal aspect of your life -- your little secret, if you know what I mean."

Mr Figaro was so cold that his teeth had started to chatter. "So you know about that, too?" he muttered feebly. "I didn't think anyone knew except me and Miss Daria --"

"There's no room for secrets in the world of today," his inquisitor broke in. "Look at the matter rationally and realistically Mr Figaro, and answer me one thing: Do you plan to marry Miss Daria?"

"No -- no," said Mr Figaro, "I couldn't do that. . ."

"Quite so," said the man in gray. "Being paralysed from the waist down, she'll have to spend the rest of her life in a wheelchair, yet you visit her every day for half an hour and take her flowers. Why?"

"She's always so pleased to see me," Mr Figaro replied, close to tears.

"But looked at objectively, from your own point of view," said the agent, "it's time wasted -- twenty-seven million five hundred and ninety-four thousand seconds of it, to date. Furthermore, if we allow for your habit of sitting at the window for a quarter of an hour every night, musing on the day's events, we have to write off yet another thirteen million seven hundred and ninety-seven thousand seconds. Very well, let's see how much time that makes in all."

He drew a line under the long column of figures and added them up with the rapidity of a computer. The sum on the mirror now looked like this:

Sleep 441,504,000 seconds

Work 441,504,000 "

Meals 110,376,000 "

Mother 55,188,000 "

Budgerigar 13,797,000 "

Shopping, etc. 55,188,000 "

Friends, social club, etc. 165,564,000 "

Miss Dana 27,594,000 "

Daydreaming 13,797,000 "

Grand Total 1,324,512,000 seconds

"And that figure," said the man in gray, rapping the mirror with his chalk so sharply that it sounded like a burst of machine-gun fire, "-- that figure represents the time you've wasted up to now. What do you say to that, Mr Figaro?"

Miss Daria is in Michael Ende’s novel something of an archetype for the physically handicapped and mentally challenged. Excessive capitalism pushes these people who are already at a society’s margin into a space where we have to spend no time with them. Industrial education systems of competitive knowledge economies do the same. They are fascist in nature and create ghettos.

I remember a befriended foreign couple who had a son the same age as our first born daughter. They left China last summer because their son had learning difficulties which could not be met in Chinese public and private education systems. Their international school informed them that their son would need special attention which the school was not able to provide, i.e. which the school was not willing to invest in.

I had met that boy several times and observed him because I was aware of the challenges his parents experienced. Nobody would have considered that boy mentally challenged at a first glance. And even after longer observation I did see only a child with a very unique and sensitive way of exploring the world.

We need to find a new form of learning. One which engages children through play and helps them to absorb information in an enjoyable manner. A form of learning which instills a sense of purpose into them; and a form of learning which teaches them compassion for self, others and the planet.

If we don’t succeed in this transformation of our educational systems, we will continue to exploit the planet and create societies with an ever widening wealth gap. We might even end up in conditions similar to what WWII brought to Europe, only in a science fiction version of a society which advocates genetic brain modifications and physical alterations.

This is the future historian Yuval Harari describes in Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow; and we are on a fast track to make it a reality. I don’t think that homo deus is a well-chosen term. Human beings who have purged their societies from play and compassion are rather the incarnation of the devil than the creator. Neither do I believe in black and white scenarios of good and evil. Life is a constant approximation towards a better self and whoever tries to understand the self, will realize that it is an interconnected part of something much larger. Let’s consider therefore paths towards a more human future.

Our species is biologically classified as homo sapiens, i.e. the wise or rational human, since about seventy thousand years. But our education systems are set up to churn out a kind of homo oeconomicus who exploits oneself, others and the planet. That’s neither smart nor wise and requires another evolutionary step, some transformation in our brains - induced by a changing environment not surgery nor genetic modification.

Industrial education systems ignore that most of us are not homo sapiens or homo oeconomicus, but rather homo faber and probably even more homo ludens. We like to play and need to play. It is through play that we become homo sapiens. Carl Gustav Jung once said that the creation of something new is not accomplished by the intellect but by the play instinct acting from inner necessity.

In reference to the earlier mentioned Merics report: quod era demonstrandum est. One can’t straddle a fine line between maintaining conformity and promoting creativity. Enlightened education destroys conformity and instills creativity. It instills compassion and destroys ignorance and apathy. Hence, Dark Age was the term we coined for periods when societies were kept in low consciousness.

There is one man who understood the importance of play at the brink of one of the darkest periods in the history of mankind. Dutch philosopher Johan Huizinga showed that play is the source of all culture and left his ideas to the rest of us in an attempt to fend off the outbreak of WWII in 1938. It might well be that we are at a similar threshold taking a swooping view of how political systems have shifted recently on a global scale.

Once the well of play goes dry, civilizations collapse and individuals suffer mental health issues ranging from procrastination to suicide.

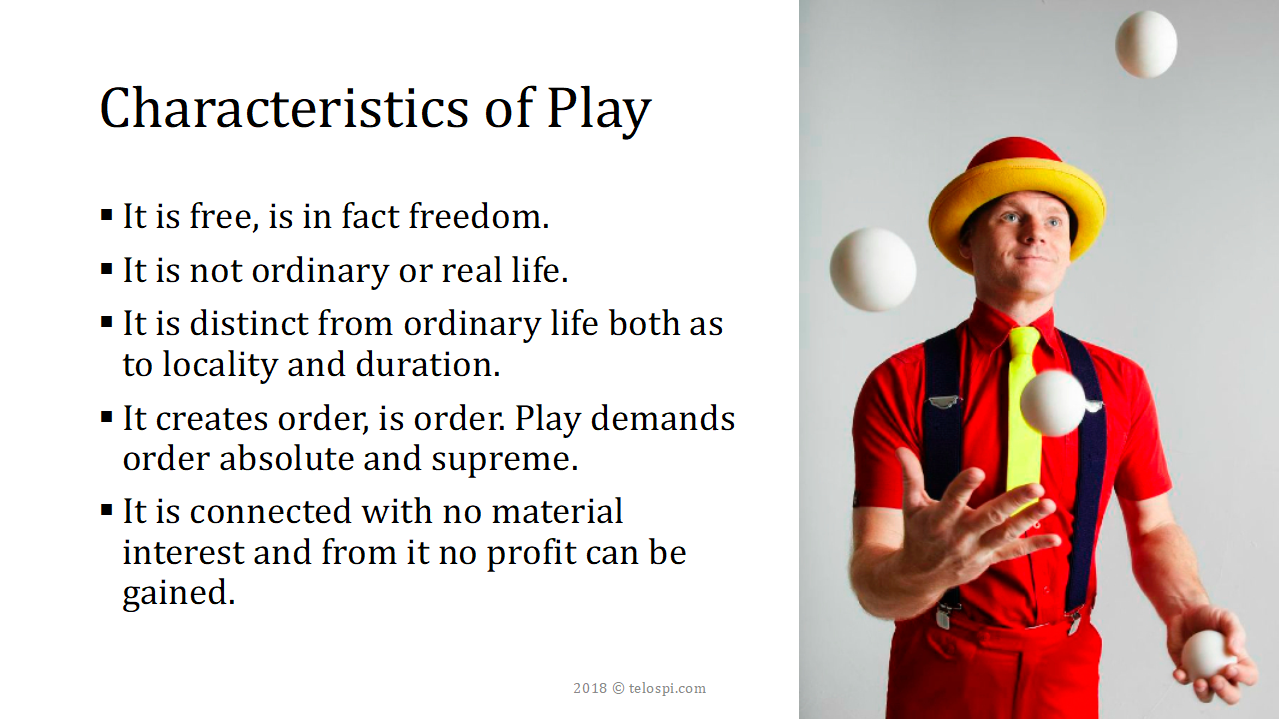

Huizinga defines in his seminal work Homo Ludens five distinct characteristics for nourishing play:

1. It is free, is in fact freedom.

2. It is not ordinary or real life.

3. It is distinct from ordinary life both as to locality and duration.

4. It creates order, is order. Play demands order absolute and supreme.

5. It is connected with no material interest and from it no profit can be gained.

It’s day four and we participate in our first excursion in an Austrian Hungarian National Park. A young guide meets us close to the shore of Neusiedler Lake. Isak is kind of disappointed because there are no other children. Only three German tourists - all of them substantially older than his father - join this walk into the only natural Austrian sand dune.

Lots of explanations don’t contribute to his experience, but I show him how to use a binocular to spot grey geese, a marsh harrier and lapwings. Later we let him take over the insect specimen collection with a large butterfly net.

It takes a while until his attention is caught, interest found, and engagement activated. Eventually its only hunger and the heat of the midday sun which make him give up his hunt. Within two hours only he has learned the names of at least ten insects, that there are different kinds of grasshoppers and that some flies are predators.

I don’t know if we met his learning needs. I don’t know if Isak will become a second Konrad Lorenz, the Austrian Nobel Laureate who conducted his research on instinct behavior with the grey geese which we see here every few meters. But does it matter? I hope he will become a kind human being enjoying whatever he will one day call his job.

Much of this is not in his hands, but in the hands of the people who define how our education systems are set up. The only legacy we can leave to him within the boundaries of those systems are

1. lots of meaningful play time.

2. Kindness to himself and others, that is love instead of fear.

3. And many parts on the table to play with.

Its fascinating that Dr. Montessori believed that play is the important work of early childhood. She placed value on children’s activities by describing and treating them as work; and combined the traditional definitions of work and play: A child’s work becomes not only an effort a child makes or a process the child follows to do something or make something that has value to the child or to the child’s environment, but also an activity the child finds enjoyable and interesting and valuable in itself for that reason.

Dr. Montessori observed that children

concentrated best when they were interested in a task; that children preferred to have order and keep order around them;

preferred real-life work over play and enjoyed to work in quiet;

learned by neither receiving reward nor punishment;

preferred to have the opportunity to correct their own mistakes;

preferred to have the freedom to choose their work and their materials and doing things by themselves.

Carl Gustav Jung once said that the creative mind plays with the object it loves. Psychologist Daniel Levitin writes in The Organized Mind that creativity involves the skillful integration of a time-stopping daydreaming mode and the time-monitoring central executive mode. Achieving such a state of mind was called by Abraham Maslow peak experiences and by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi flow.

During flow, two key regions of the brain deactivate: the portion of the prefrontal cortex responsible for self-criticism, and the amygdala, the brain’s fear center. You cease thinking about yourself as separate from the activity or the world, and you don’t think of your actions and your perceptions as being distinct – what you think becomes what you do. Another thing that characterizes flow is a lack of distractibility – the same old distractions are there, but we’re not tempted to attend to them. Engagement is what flow is defined by – high, high levels of engagement. Levitin writes that something paradoxical occurs in the brain: we do no longer exert ourselves to stay on task – it happens automatically as we enter this specialized attentional state.

There seems to be a strong overlap between peak experiences or flow with what Maria Montessori described as normalization. The only difference is that Montessori described a state of mind pertaining to children, while all other mentioned psychologists describe a state of mind pertaining to adults. This raises the question whether the prefrontal cortex really plays such an important role as the latter have assumed. The PFC is the last part of the human brain to mature and it does so up into the early 20s.

It seems that the amygdala plays a much bigger role indicating that fear or lack of trust is the essential factor obstructing a child (and an adult) to enter normalization or flow respectively. We therefore need to put an emphasis in our societies on creating trust and an atmosphere of compassion. Modern knowledge economies do the opposite: they question the existence of the human being which can be substituted by robots and algorithms.

Montessori coined a term for how children maintain this state of normalization: joyful obedience. While cognitive psychologist Levitin understands the brain chemistry of flow, Montessori understood how to achieve this state of mind in highly disturbed children. She focused her work on developing self-discipline through manual activities and observed that children under 3 are not able to obey for intrinsic reasons.

Children between 3-6 enter the second level of obedience and can obey, however, their obedience is extrinsically motivated and they obey blindly without thought or question. The third level of obedience or joyful obedience is entered after age 6 when children can complete what is asked of them, and more importantly, they see value in doing so. Joyful obedience and normalization coincide.

Understanding that Montessori did essentially describe for children what Csikszentmihalyi explained for adults is significant, because it means that normalization is a habit which is ideally fostered during early childhood. Children who achieve joyful obedience early on will become creative adults who find satisfaction in their work and thus freedom from addiction.

One of the most important characteristics of the practical life activities is that they allow children to develop their independence, which helps them to achieve freedom – a cornerstone in Montessori theory. Dr. Montessori believed that children require freedom of choice to develop independently and become the people they are meant to be, i.e. unfold their true creative potential.

Montessori’s terminology of work and play does echo Jung’s explanation of how creativity takes place: A child’s work becomes not only an effort a child makes or a process the child follows to do something or make something that has value to the child or to the child’s environment, but also an activity the child finds enjoyable and interesting and valuable in itself for that reason.

It is also important to recognize that for both children and adults anxiety is a result of extrinsic coercion while boredom is caused by a lack of intrinsic obedience. Integral to Montessori’s concept of freedom is the necessity of limits. While Montessori believed it was imperative for the child to function freely in the prepared environment of both classroom and home, she understood that the child must first learn how to behave in these environments though practical life grace and courtesy activities.

Freedom from anxiety and boredom is the result of normalization and as such threading a territory which Montessori explored with children through manual work: The transition from one state to the other always follows a piece of work done by the hands with real things, work accompanied by mental concentration. The same is true for adults who suffer both under limitless freedom and the yoke of oppression. It is through manual work that normalization can be achieved.

The French Anthropologist Andre Leroi-Gourhan recognized early on the importance of manual work and the danger involved in digitalizing societies. He wrote that it would not be particularly important to mention that the importance of the hand diminishes, if this activity were not closely related to the balance of brain regions associated with it. Being unable to think with his hands means losing part of his normal and phylogenetic human thinking.

While people used to touch almost everything, they now touch only a screen and thus their minds get crippled. This is yet another argument for why Dr. Montessori’s practical life activities are more important than ever as long as they merge for children the traditional concepts of work and play.

Our first pitstop in Vienna is with writer Andreas Kurz. We became friends when he worked in Shanghai a few years ago and ever since I enjoy a chat with him now and then. His new life after a few years in Moscow has taken shape in the Austrian capital and we visit him in his suburban house, which he rents with an architect and a shiatsu therapist.

He tells me that his little garden in the back of the house fills him every morning with delight. Andreas has established at age 39 a new habit. His monkish life style makes him get up every morning 5am to write on his second book, a novel. But before he leaves his house to start his day job, he spends half an hour tending to his plants and crops.

I observe him early next morning and above paragraphs come back to my mind. It is certainly manual work which guarantees a cognitive equilibrium. Whether the work done by the hands with real things needs to be accompanied by mental concentration, as Dr. Montessori wrote, I doubt though.

This might be true for children in the phase of the absorbent mind, but afterwards and in particular for adults it is enough to chip some relaxing manual work in between periods of mental concentration. Those who can merge manual and mental work like sculptors or surgeons are rare exceptions nowadays. However, increasing automation will make it likely that a large part of the next generation will spend its working hours as artisans and skilled craftspeople.

The amount of manual work which we need to feel whole and sane varies from one person to another; and I am convinced that our knowledge economies need an overhaul. Competitive knowledge economies push everybody into highly specialized mental work and thus create misery for the individuum and society.

The individuum turns into a dull automaton and loses its normal way of thinking as anthropologist Andre Leroi-Gourhan writes. Society and its labor markets are on the other hand deprived all of all the skilled labor it needs to function well. Skilled labor shortages in almost all industrialized nations confirm this statement. The US experiences a widespread worker shortage and wealthy EU countries struggle since years with worker supply which has been only compensated with immigration.

We leave Vienna and Andreas Kurz’s home the next morning and drive to a small village about 35km north of Vienna where one of my best friends whom I know since elementary school celebrates his belated wedding. An Austrian-Czech band plays in a jazzy Flamenco style while the sun torches the wedding location. All guests but Isak seek the shadow of the tents and the proximity to the bar.

I meet many people I haven’t seen for years and we chat about our lives, football and politics. When I ask a high school friend and his wife about their children, they tell me that their oldest has decided to start an apprenticeship as bricklayer. There is a moment of awkwardness and the father fills the silence by asserting that he is glad that his son has made this decision because further academic training would have been the wrong path.

We still have to go a long way in our societies to appreciate such career choices. Not only because our education systems still push everybody into academic thinking, but also because we still do not respect manual work the way it deserves to be respected.

Moreover, most economies don’t pay their manual workers well enough. They are being exploited.

Our second excursion into the Austrian Nationalpark Seewinkel takes us on a solar-powered boat around the lake and deep into its reed belt. Our guide Ruth explains us a great deal about the lake ecosystem using a large map. Adults listen, but I observe that the three participating children aged 4 to 6 are bored.

It is only when Ruth starts to explain the lake’s fish population by moving to a big bucket full of water and covered with a lid that the kids wake up – in particular Isak. Ruth tells us that her team paralyzed a few fish early this morning in the lake with a light electroshock and caught all of them in this bucket. Everybody is invited to identify the catch.

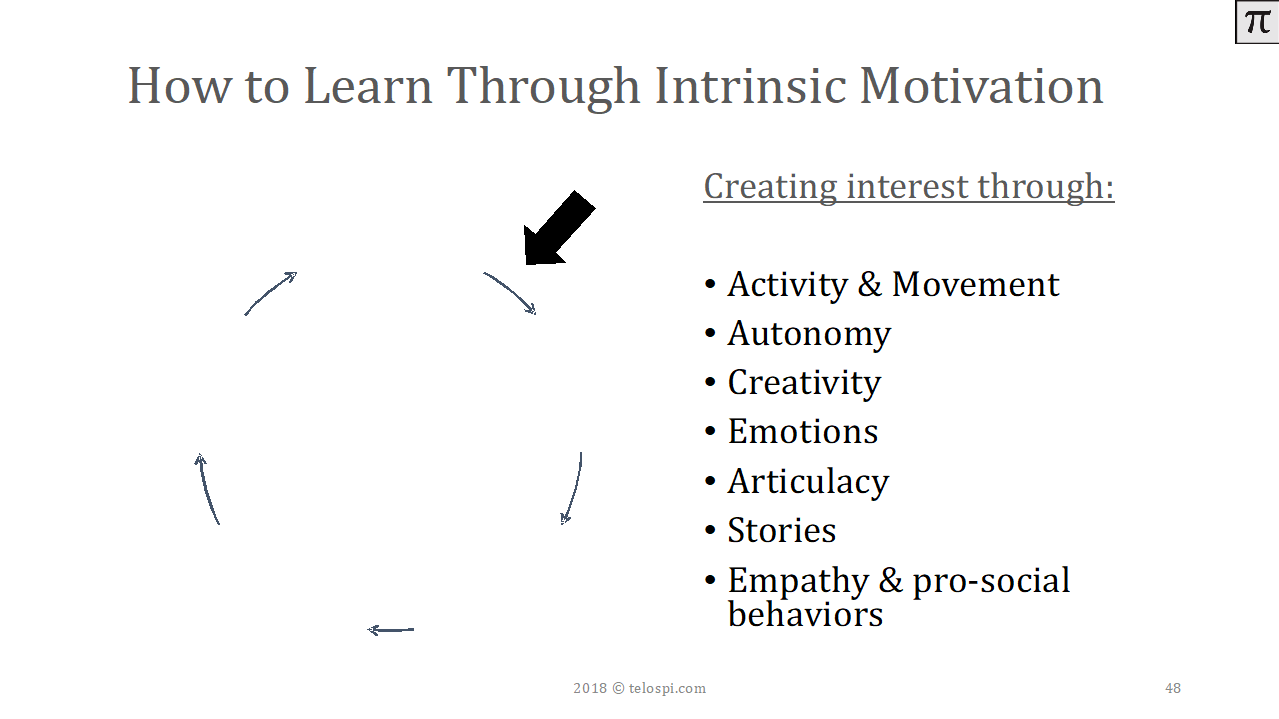

Adults don’t move, but children jump at the bucket and stay mesmerized for a far longer than the usual attention span. They are invited to use small fishing nets to catch single fish for identification and discuss with the guide size, color, scale patterns and position of fins. Its apparent that interest, attention, engagement and obsession are merged into a single prolonged moment. Why is that?

It seems that the fish identification activity hit the sweet spot for intrinsic motivation of learning. Let’s take therefore a closer look at the activity and let’s try to isolate its design elements.

It’s certainly playful.

It is manual and practical using various senses.

Its taking place outdoors and is in connection with nature.

Its non-competitive and has a collaborative character.

The learning content is novel.

It’s guided under certain frame conditions and establishes limits to freedom.

It is designed for a prepared environment

It’s designed with an element of mystery: what is in the container?

British teacher and researcher Debra Kidd spoke in Shanghai in 2017 on intrinsic motivation. She explained that it is crucial for successful learning to create attention and shift from attention to interest. Her above list of how to create interest is quite complete. I am surprised though not to find play on it. Play would encompass all the above attributes.

Maria Montessori has at a time, when we were not yet able to explore the neurology of learning, already understood the process of purposeful and joyful learning, of how to guide a child into unfolding its potential. I have struggled over the past few years to wrap my mind around the question of how we can instill into adults and children an interest in life which naturally guides them towards a fulfilled profession and turns them into balanced and responsible human beings.

Montessori has turned into a towering lighthouse for me. But I have also noticed that most Montessori kindergartens and schools have perverted her teachings into an empty shell very much like Christ’s teachings have been converted into an empty dogma by fundamentalists who stick to the written word instead of the meaning behind.

Economist Andrew McAffee, who attended a Montessori school himself, and educator Ken Robinson have also asked themselves what it takes to unfold the human potential and get people engaged in their professions. Both arrive – despite coming from different disciplines – at the conclusion that education is the key to resolving many if not all challenges which humanity faces at this point of evolution.

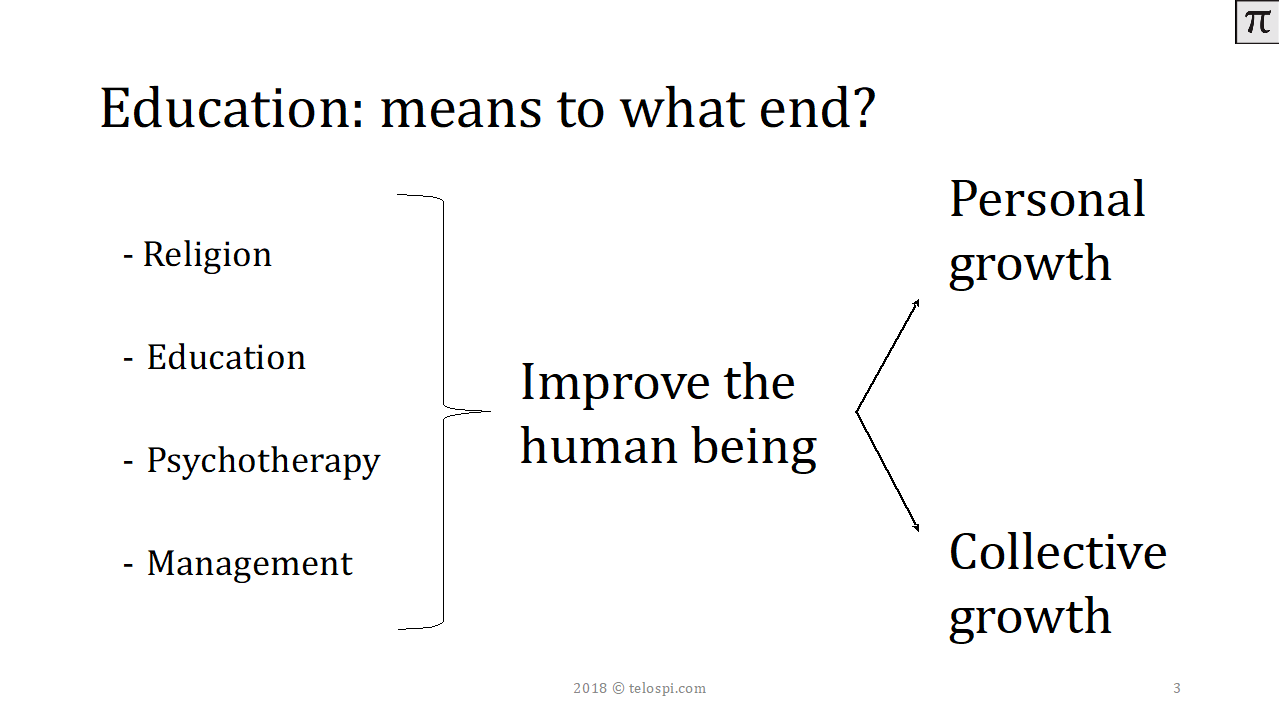

The lock into which we have to put this key is nevertheless not the individuum, but our societies and yes, our species at large. Education, and the same is true for religion, management and psychotherapy, is a means to a specific end: improving the human being in order to achieve collective growth.

Personal intellectual growth has turned into an obsession, which is driven by the fear of being left behind. We push our children into academic training and deprive them of play. We don’t do this because we love them, but because we consciously or unconsciously fear that they might lose this rat race. Could it be that 400 years of capitalism have made us confuse love with fear?

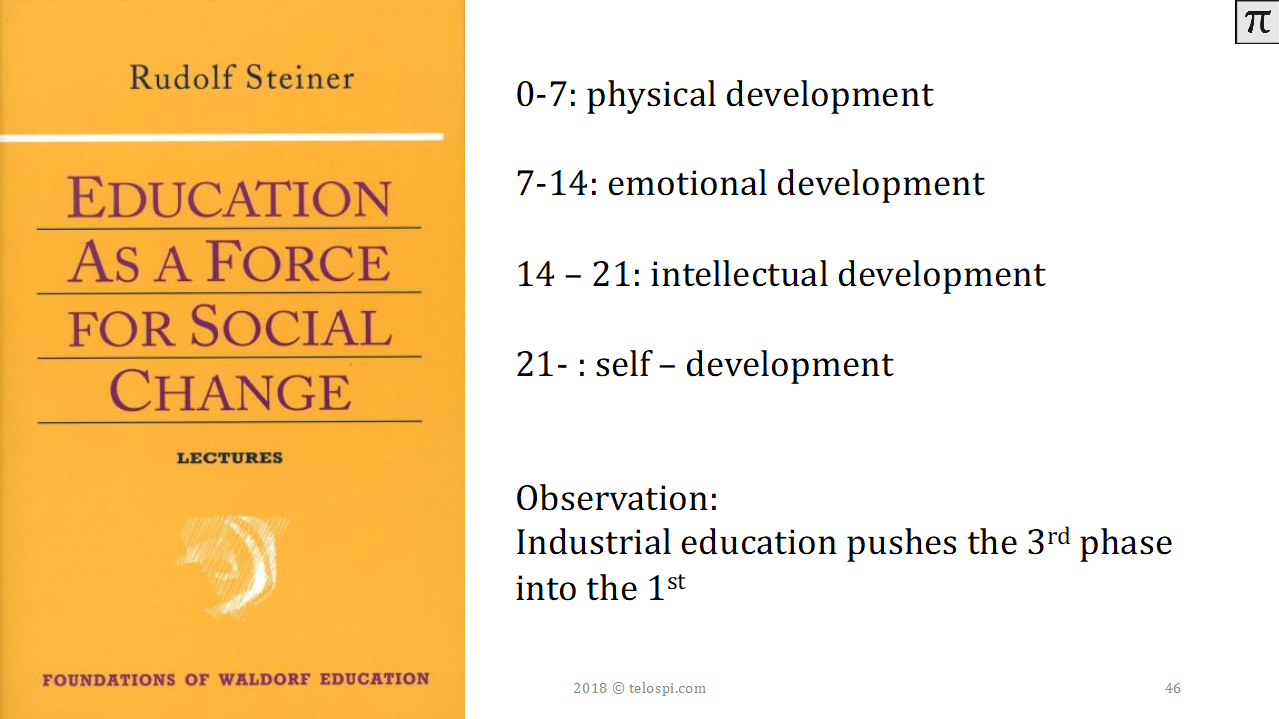

The discussion about the appropriateness of kindergarten graduation ceremonies is a firm indicator for this development. Gathering children who have barely emerged from their toddler age to celebrate the graduation in the gown of university graduates reflects that industrial education pushes intellectual training into the period of physical development.

Philosopher Rudolf Steiner, the founder of anthroposophy, had a similar concept like Maria Montessori for human development psychology, describing four distinctly different phases. Comparing the two 20th century educational reformers, I have arrived at the conclusion that Montessori excelled in explaining the patterns of infancy and early childhood, while Steiner mastered late childhood and adolescence.

Both, Steiner and Montessori would agree with the analysis that industrial education pushes the third phase into the frist. Modern mainstream education creates morons.

It is on the last leg of our journey, when we board in Moscow the China Eastern plane to Shanghai, that we reenter the gulag culture: one which is mainly established through extrinsic coercion instead of intrinsic motivation. The crew manager announces in Chinese and English that according to Chinese aviation safety law, passengers who ignore crew instructions or safety regulation will be fined, kept in detention and are subject to criminal prosecution in case of serious violations.

I have never heard such an announcement in any other airline and to me it reflects one tiny aspect of a totalitarian governance which conceives the citizen as a subordinate subject only, who must be controlled by all means. It is this relationship between the state and the private citizen which China must resolve if she wants to evolve.

The next step in our evolution must not be homo deus like Harari anticipated, but should be homo illumens. Its either this or we are ought to perish as a species. We need to design a culture which conditions humans towards purposeful work and a truly interconnected and compassionate attitude. In order to get there, we need to shift focus back to mindful and free play.

SOURCES

Gary Snyder: The Practice of the Wild

Gerald Hüther: Singen ist „Kraftfutter“ für Kindergehirne, Zeitschrift Frühes Deutsch, Heft 13, 17. Jahrgang, 2008

Damien Ma and Adam Walker: In a Line Behind a Billion People

https://www.merics.org/en/china-monitor/manufacturing-creativity-and%20maintaining-control

https://www.nachrichten.at/oberoesterreich/in-englisch-und-mathematik-sind-unsere-maturanten-oesterreichweit-spitze;art4,3137973

http://www.mingong.org/blog/nature-classroom-of-the-future

Ken Robinson on divergent thinking

Steven Johnson: Where Good Ideas Come From

Maria Montessori: The Absorbent Mind

Ken Robinson: The Element

https://www.welt.de/print/die_welt/wissen/article125239452/Genie-ist-kein-Zufall.html

https://www.vox.com/2019/3/18/18270916/labor-shortage-workers-us

Larisa Shavinina: The Innovation Handbook

http://www.ted.com/talks/mihaly_csikszentmihalyi_on_flow

Johan Huizinga: Homo Ludens

Michael Ende: Momo

Daniel Levitin: The Organized Mind

https://www.technologyreview.com/s/612458/exclusive-chinese-scientists-are-creating-crispr-babies/

Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow

Wilhelm Reich: The Mass-Psychology of Fascism

https://www.ted.com/talks/andrew_mcafee_what_will_future_jobs_look_like/transcript

https://www.ted.com/talks/sir_ken_robinson_bring_on_the_revolution

Do four-year-olds need a graduation ceremony?

http://www.darkmatteressay.org/the-challenges-of-rudolf-steiner-2011.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whisper_of_the_Heart

http://www.sixthtone.com/news/1001708/starting-from-scratch-chinas-dj-kids#